There have been cases of two-headed sharks in the past, but reports indicate they are all of the same breed as giving birth. The researchers are now learning more about this individual and hope to uncover the cause of this mysterious dicephaly.

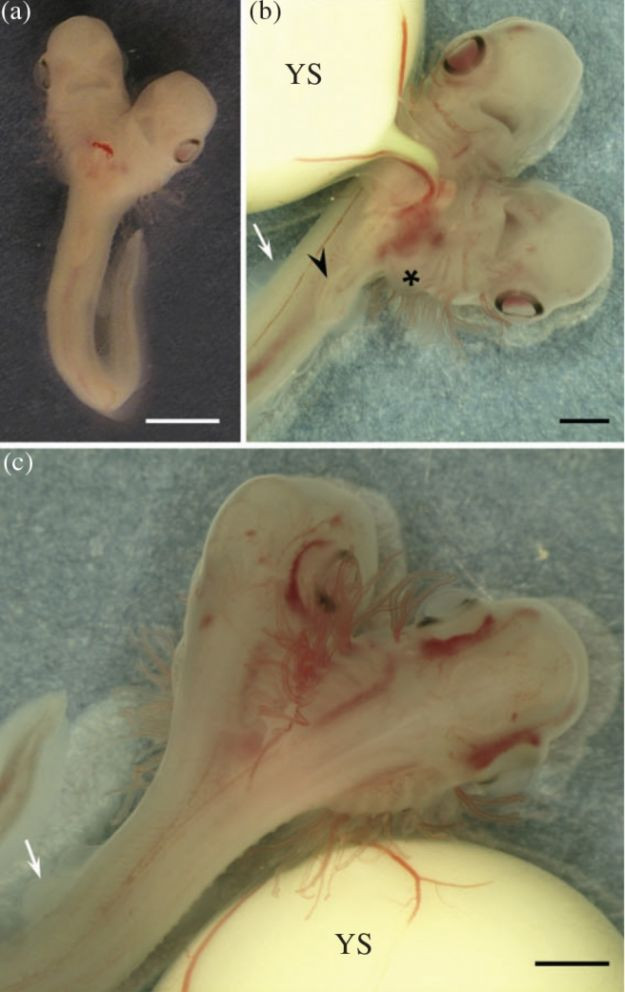

This embryo belongs to the Atlanta saw-tailed cat shark (Galeus Atlanticus), collected by scientists at the University of Malaga – Spain to study the cardiovascular system. Of the 797 embryos collected, one was distinct from the others: it had two heads. “Each head has a mouth, two eyes, a brain, a spinal cord, five scales on each side,” the authors wrote in the Journal of Fish Biology.

This embryo body also has 2 hearts, 2 stomachs, 2 livers, but only 1 set of intestines, kidneys, and genitals. This is not the first time two-headed sharks have been found – there are seven reports in the scientific literature of two-headed sharks.

However, all of the above reports include sharks of the reproductive breed, while the cat shark is the first egg-laying shark to exhibit the dicephaly mutation – and this could be the key to helping us understand. the cause of this trait.

This individual has been kept so that scientists can study it more closely. In the wild, cases like this are rare and it’s not clear whether it’s rare because of probability or simply that two-headed individuals are unlikely to survive long enough to be detected.

Historically, people have discovered snakes, two-headed cats and even humans. “They can survive birth, but there’s a high probability that their lifespan will be very short,” Michelle Heupel, a researcher at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, told Hakai magazine. “It’s not clear if having two heads interferes with the ability to swim or hunt, or if internal organs will function properly.”

The good news is that the cause seems to be mutations, not environmental pollution like in The Simpsons. The researchers say there is no mutagenic agent in the chamber where the embryos develop.

“Every once in a while we find a two-headed shark. It’s a genetic variation. Most don’t come out alive.” According to George Burgess, director of shark research at the Florida Museum of Natural History, told National Geographic.

It’s not clear whether the cause of the mutation in spawning sharks and calving sharks is different, but hopefully research conducted on this embryo will give us the answer.